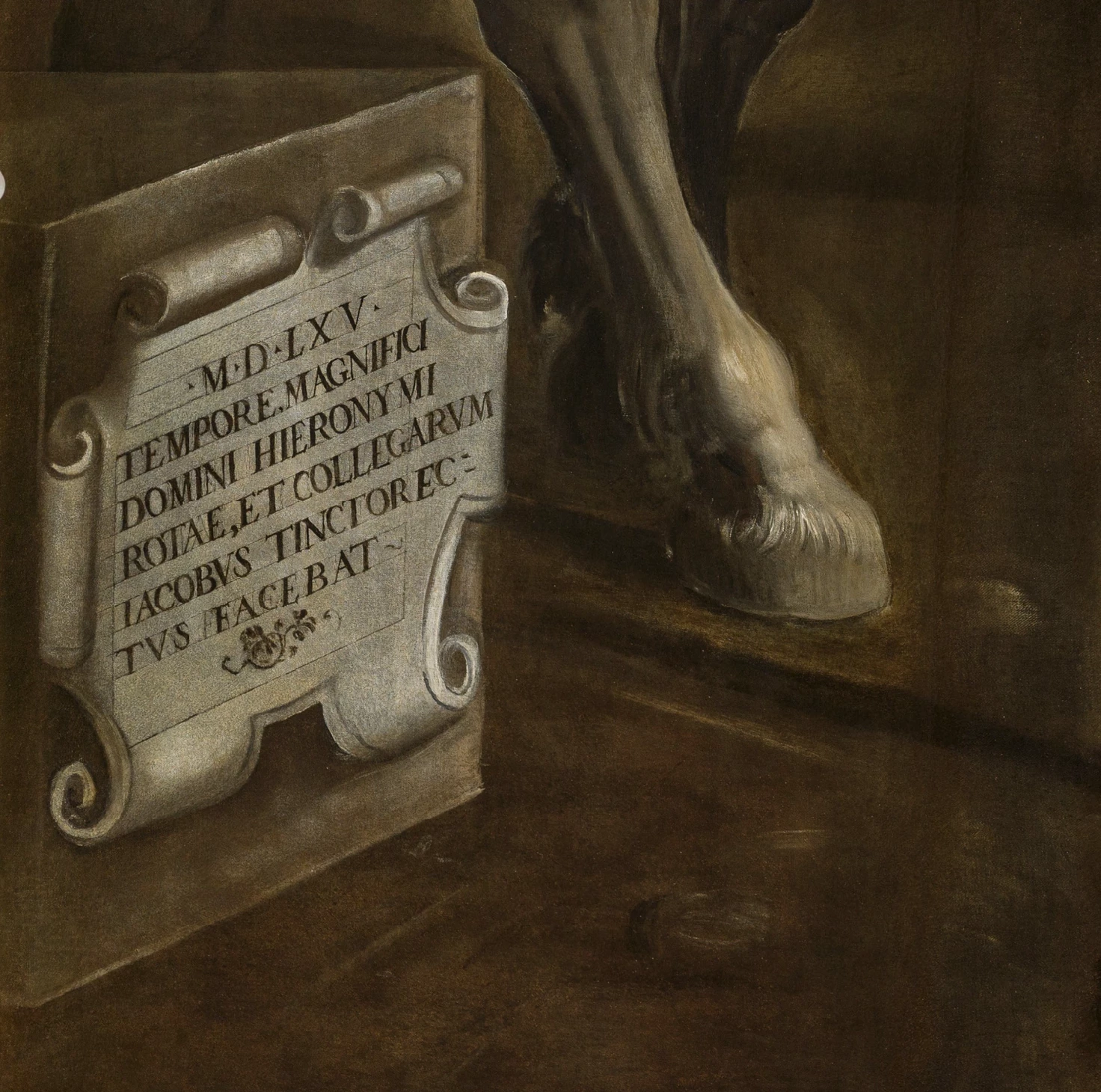

Tintoretto’s Crucifixion is widely regarded as one of the greatest masterpieces of Renaissance art in Venice—perhaps second only to Titian’s Assunta, if it can be considered second at all. Measuring more than five meters in height and over twelve meters in width, the vast canvas dominates the wall above the banco, the wooden desk behind which the confraternity’s officials once sat and from where they oversaw the daily administration of the confraternity. The painting was completed in 1565, the very year Tintoretto became a member of the Scuola. By the time he received the commission for the Crucifixion, Tintoretto had already painted Saint Roch Healing the Plague-Stricken (1549) and Christ at the Pool of Bethesda (1559), and the painted ceiling of the Scuola’s boardroom (1564), the latter partially conserved with support from Save Venice between 2008 and 2009. On 9 March 1565, he received the final payment of 250 ducats for the Crucifixion. That same year, he signed the canvas at the lower left: “1565. At the time of magnificent Girolamo Rota and brothers. Jacopo Tintorectus.” This dedicatory inscription underscores the crucial role of Guardian Grande Girolamo Rota, the Scuola’s chief official and one of Tintoretto’s most influential patrons.

Tintoretto must have produced dozens of figural studies before finalizing the composition of the Crucifixion. One particularly striking example is the study of a mourning woman at the foot of the cross (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence), where the artist focuses not only on the intricate, swirling folds of the drapery but also on the twisting anatomy beneath it. Another compelling sketch, now in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, depicts a male figure leaning downward to the left—likely a preparatory study for the man bending from the ladder to dip the sponge in vinegar. Scientific analysis carried out during the previous conservation treatment of the painting in 1972 revealed that Tintoretto sketched his composition directly onto the canvas, first mapping out nude figures and then layering painted draperies over them. Several unfinished works, such as the Holy Family with Young Saint John the Baptist, (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), confirm that this method was typical of Tintoretto’s practice. The approach was even passed down to his son Domenico, whose Fidelity at the Harvard Art Museums clearly shows the same creative process at work.

To conceive such an immense and densely populated composition, Tintoretto drew inspiration from his earlier Crucifixion in the Accademia Galleries—a painting originally made for the Scuola del Sacramento in the Venetian church of San Severo and restored by Save Venice in 2018. The influence of the San Severo painting can be seen in several key motifs: the centralized figure of Christ, the mourning group gathered beneath the cross, the soldiers casting dice, and the elegantly posed horsemen at either side of the scene. Yet, for the Scuola di San Rocco, Tintoretto refined and expanded his approach. He created a composition that is at once more monumental and more legible. By placing Christ high at the upper edge of the canvas, he established a strong visual anchor that brings order to the surrounding action. He then cleared and opened the foreground, allowing a series of distinct narrative moments to unfold simultaneously without descending into confusion. These episodes—each carefully separated by spatial intervals—include the soldiers casting lots for Christ’s garments, the mockery of Christ, the offering of the vinegar-soaked sponge, and the Virgin Mary’s collapse into a swoon. Together, they form a choreography of movement and emotion that reveals Tintoretto’s extraordinary ability to orchestrate drama on a grand scale.

Two additional episodes in the composition merit special attention. On the right-hand side, the Bad Thief lies on the ground, his back turned toward Christ—a figure already condemned, his fate sealed even before he is lifted onto the cross. On the opposite side, the Good Thief is being raised aloft, his gaze fixed on Christ in a final moment of recognition and faith. In this exchange, Tintoretto gives visual form to Christ’s prophecy: “And when I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw everyone to myself” (John 12:32). Scholars have long noted that Tintoretto, much like in traditional depictions of the Last Judgment, appears to divide the composition into two symbolic realms: to Christ’s left, those who reject or fail to understand the Revelation; to his right, those who respond to it with openness and belief. Within this framework, the Roman centurion on the white horse at Christ’s right—shown in the very act of recognizing Christ’s divinity—takes on added significance. Many have proposed that this figure is a disguised portrait of Girolamo Rota, the Guardian Grande of the Scuola and the powerful patron who commissioned the Crucifixion.