Introduction

Every conservation project begins with an essential step: understanding. The study of the material aspects of an artwork, supported by scientific investigation and multispectral diagnostics, produces a collection of technical data revealing the artist’s working methods. This acquired knowledge forms the basis of every subsequent conservation action. Analyzing and interpreting the materials used for a painting, sometimes mere traces, allow a conservator to align with the artist's intentions and understand their creative process, while catching a glimpse of the path that guided the artist’s hand. Every indication of damage, and subsequent intervention, reveals a fragment of history: not only that of the artwork and its creator, but also of the events that have marked the painting’s surface over the centuries.

The conservation of Tintoretto’s monumental Crucifixion provided a rare opportunity to approach both restoration studies and conservation treatment in a unified and organic way. This experience led to the core of the artist's workshop where the painting was produced, unveiling the complex endeavor that Tintoretto conceived as a collective process from the outset. Similarly, a conservation worksite is a place of intense study, activity, and research: a collaborative effort of meticulous work conducted in stages, in constant dialogue with the artwork and with respect for its constituent materials and its past history.

Conservation History

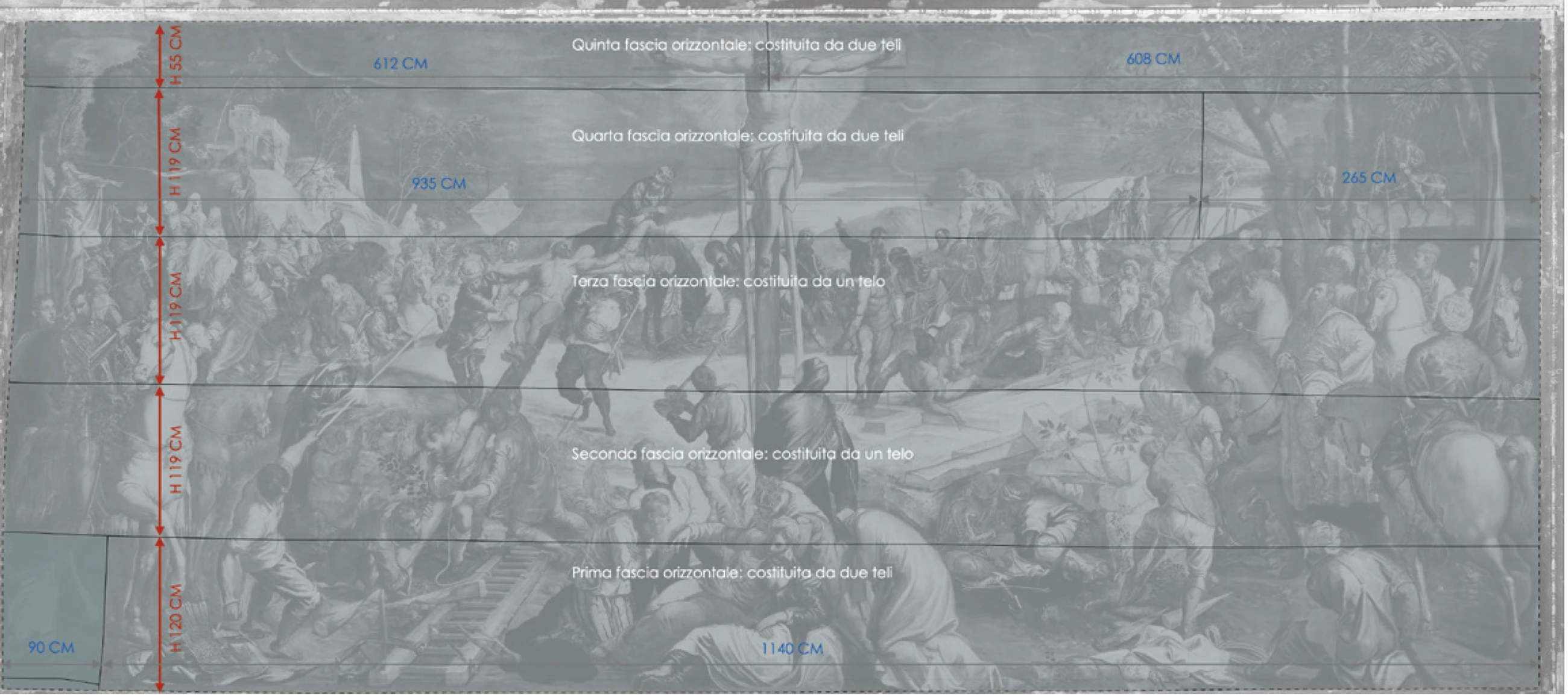

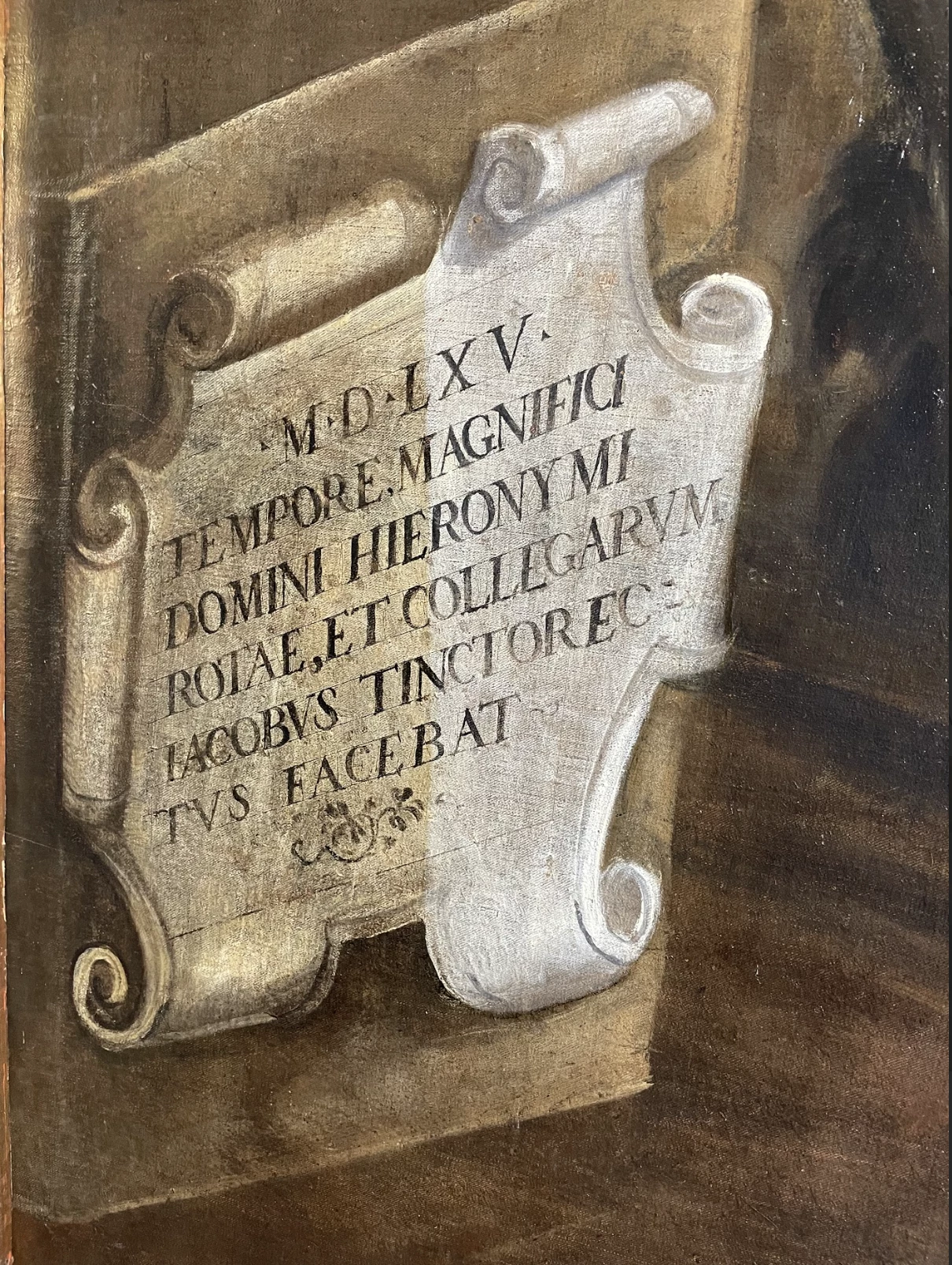

According to documentation in the archives of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, the Crucifixion underwent four conservation treatments since its unveiling in the confraternity in 1565, including the most recent one that was completed in 2025. The painting was taken down at least five times from its position on the wall of the Sala dell’ Albergo, a complicated operation in itself, due to the large dimensions of the canvas Tintoretto painted, measuring over 5 meters in height and 12 meters in width (530 cm x 1230 cm).

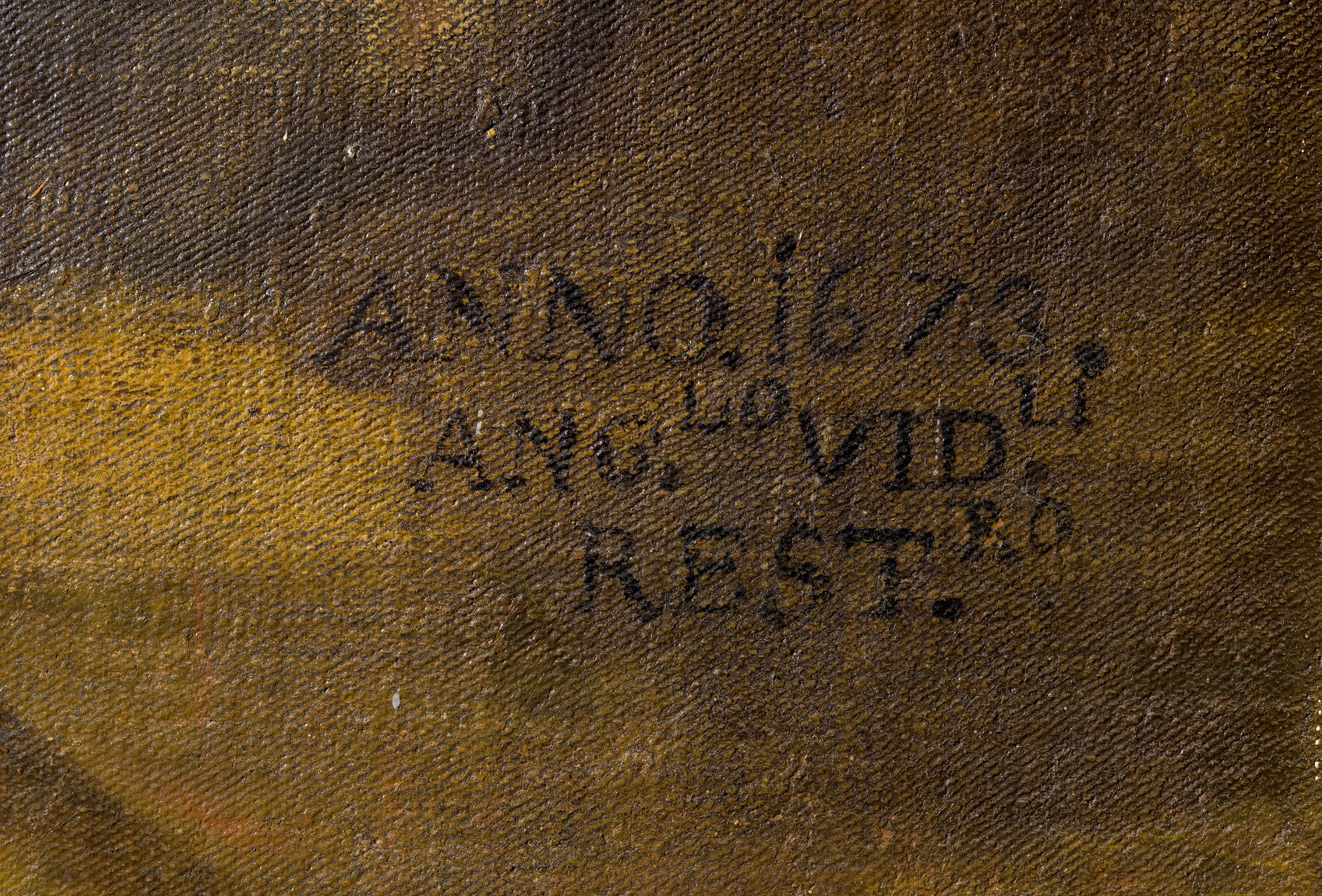

The first documented restoration campaign dates to 1673 when the Crucifixion was damaged by rainwater from a leaking roof and suffered from the dampness of the wall behind it. Restorer Angelo Vidali applied a canvas lining to the painting to increase the tension of Tintoretto’s original fabric support and cleaned the painted surface to “wash mold”. Vidali’s work is commemorated on Tintoretto's painting with an inscription located on the lower register at the far right, under a horse’s hoof. In 1741, the confraternity members paid Giovan Battista Gafforelli 300 ducats to replace the wooden paneling in both the Scuola's Sala Capitolare and the Sala dell’Albergo; we can imagine that this was the second time the Crucifixion was moved.

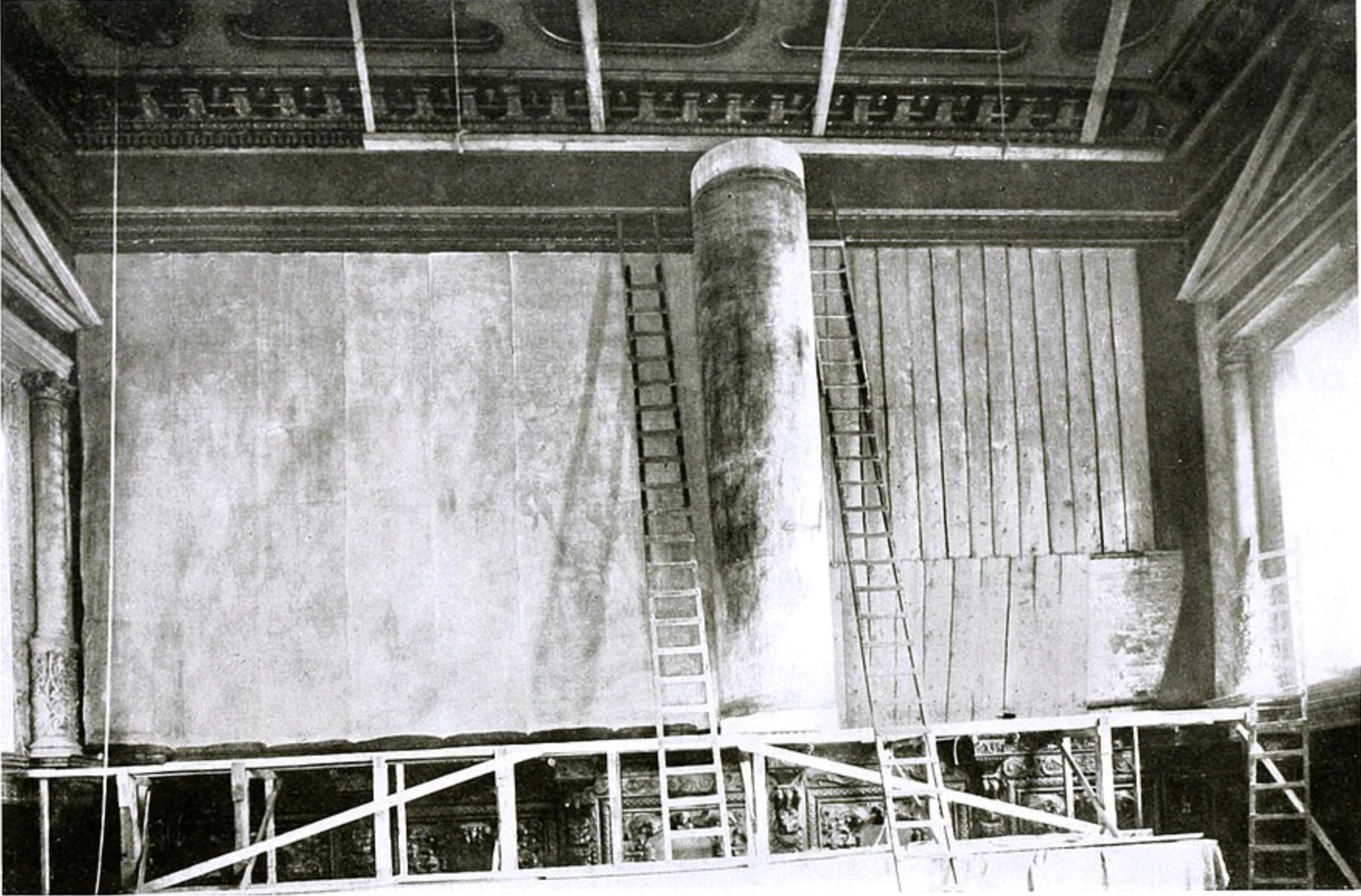

In an effort to safeguard Venice’s artistic patrimony during the First World War, in 1915 the Acerbi firm took the Crucifixion off the wall and rolled it for transport and storage. Along with 63 other paintings from the Scuola, on September 22, 1916, it was taken to Florence and placed in the Palazzo del Bargello next to Palazzo Vecchio for safekeeping. Only in 1919 did the painting return to Venice, although it remained wrapped and rolled for another three years. In 1921 the Acerbi firm, responsible also for its initial dismantling before the war, undertook the conservation treatment of Tintoretto's masterpiece. Documentation states that the procedures included "lining with a special hemp canvas, consolidation of the oxidized parts special washing, and varnishing.” Conservation treatment concluded in May of 1922 with the tensioning of the wooden perimeter strips protecting the sides of the canvas and the replacement of the boarding on the wall behind the painting.

Following Italy’s entrance in World War 11, on July 6, 1940, the Superintendent of Fine Arts of Venice Gino Fogolari activated emergency procedures to close museums and buildings of artistic and historical interest, and to begin the process of packing artworks. It is thought that at this time the Acerbi firm once again confronted the deinstallation of Tintoretto's canvases at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco so that they could be consigned to the Reali Gallerie, where they remained until the liberation of Venice and the surrender of the Axis powers in Italy in the spring of 1945. No conservation treatment is recorded in the years immediately after the paintings' return to the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. Perhaps they remained untouched because their conditions were waiting to be evaluated, or nothing was done due to a lack of funds, or there were other priorities after the war.

It was not until 1972 that the Crucifixion underwent another conservation treatment, along with 38 other paintings from the Scuola in a campaign that began in 1969 at the hands of conservator Antonio Lazzarin with funding from Edgar J. Kaufman and International Fund for Monuments. The painting once again was plagued with flaking paint and showed signs of damage because it had remained rolled for five years at the time of the Second World War. In addition, the historic "acqua alta" tidal flooding of November 1966 caused a detrimental increase in the humidity in the walls of the Scuola. Lazzarin removed Tintoretto's picture from the wall and, for the third time in its history, relined it for additional support with a double canvas adhered with traditional flour paste. The surface of the painting was cleaned, areas of losses of original paint were inpainted, and a final coat of protective varnish applied.

The most recent conservation treatment took place from March 2023 to March 2025 and was entrusted to the CBC Conservazione Beni Culturali firm, with funding from Save Venice through the generosity of donor Arnold M. Bernstein.

Data on Work Methods

Support and Preparation

Technical investigation conducted before and during treatment provided invaluable information on Tintoretto’s working methods employed to construct and paint the Crucifixion. The painting's canvas support is made up of eight pieces of linen twill with a pattern of parallel diagonal rib. The various pieces are joined together with a continuous stitch to form five large horizontal bands running the length of the painting. The fabric of the first canvas piece at the lower left is an insert, bearing the cartouche with the date, commissioner, and signature of Tintoretto, and is made with a twill of a denser weave compared to the other seven pieces.

To prepare the canvas to receive paint, Tintoretto used gesso mixed with a protein binder, presumably animal glue. On top of this is a priming layer applied to reduce the absorption of the oil in the binders used to mix the color pigments. This imprimatura is made up of a very thin (circa 10 micron) layer of tinted natural earth pigments, lead white pigment, carbon black, and another pigment composed of lead, mixed with high levels of oily binder. The composition of the pigments used as primers seems to vary according to the function of the different color fields or of the dominant color tone in each area of the picture. The lack of uniformity of the base preparation suggests that the canvas was painted in sections that we can compare to the giornate in fresco painting, indicating the amount of gesso plaster extended for one day’s work. The primer Tintoretto applied is so thin that the weave of the canvas is visible throughout the painting’s vast surface. The smoothness of each color field cannot be attributed to the thickness of the ground preparation, but instead to pigments that are rich in binders applied in thick layers. For example, the drapes of clothing painted with blue ultramarine pigment, used in a pure or mixed form, suffer from various types of craquelure due to the high oil content of the binder.

Color Palette

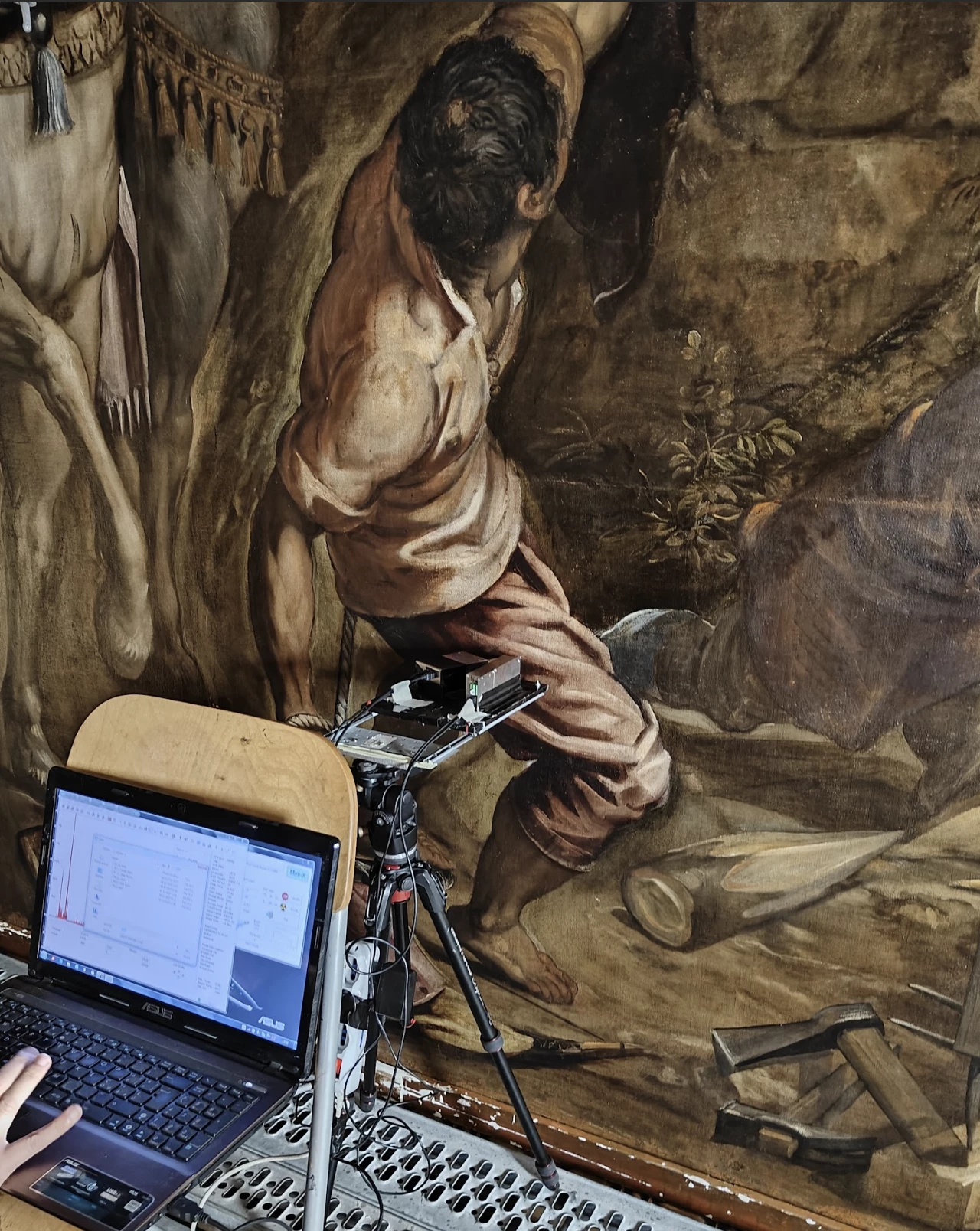

Tintoretto's original color palette and pigments were identified through X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, a non-destructive technique that determines the elemental composition of a material by measuring the unique X-rays emitted when a sample is exposed to an X-ray source. Additional studies took place using fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS). Cross-sections of pigment samples analyzed during the 1972 conservation treatment were also reexamined.

The color gamut is extremely varied, with an ample use of lead-based pigments such as white lead, minium (known also as red lead), and litharge of a yellowish or reddish hue. Red lakes (soluble vegetable or animal dyes) are present, as well as copper resinate used to form greens that have unfortunately now altered to brown. For Tintoretto's blue hues, he used precious ultramarine made from ground lapis lazuli, as well as blues formed from ultramarine ash (blue-grey), azurite (deep blue), and the more economical blue smalt. The painted areas containing blue smalt, a pigment made from potash glass, have altered in both composition and tone, turning dark and at times brown or even greyish yellow. This is due to the fugitive nature of blue smalt caused by the incompatibility of the pigment with an oil binder, which eventually causes potassium leaching that leads to color loss well as chemical and physical changes to the paint film.

Indigo was used as an intermediate color, topped off with other pigments, while violet shades were derived from ultramarine mixed with red lake. Browns come from natural earth pigments and red-brown ochre, while green earth pigments and malachite create greens. The yellow hues are made from orpiment and realgar when the tones are more orange, and giallolino (a pale-yellow pigment used for colored glass) for the more delicate tone. The synthetic pigment known as Naples yellow is also present. The presence of silica powder has been identified along with lead white and giallolino in Christ's skin tones. This was most likely added to give more luminosity to the hues and to also facilitate grinding of the harder pigments. The use of vermillion and cinnabar (a form of mercury) is somewhat limited, and reserved for the most intense reds, such as Christ's blood.

Tintoretto used dark or light color zones on the primer layer of his painting, varying according to the pigment he intended to later use or the transparency he wanted to achieve. On the dark backgrounds, he sketched out the figures and drapery, drawing with large brushstrokes with a lighter shade, using lead white to indicate the positions of the bodies and the folds of the clothing. For some figures appearing on top of areas already painted, the artist extended a light-colored layer, in particular where later he would apply red lake pigments. This is the case, for example, of the character standing under the cross and seen from the back while holding a basin of vinegar, painted on top of the earlier-painted grass, although difficult to see because the pictorial surface is damaged. This technique gave the red lakes a particularly transparent and luminous caste. In other situations, the background seems very dark, even when finished off with light tones. Small paint losses on the pictorial surface that exposed the paint layers beneath offered a precious opportunity to see Tintoretto's creative process up close.

Changes from Drawing to Painting and Corrections During the Pictorial Phase

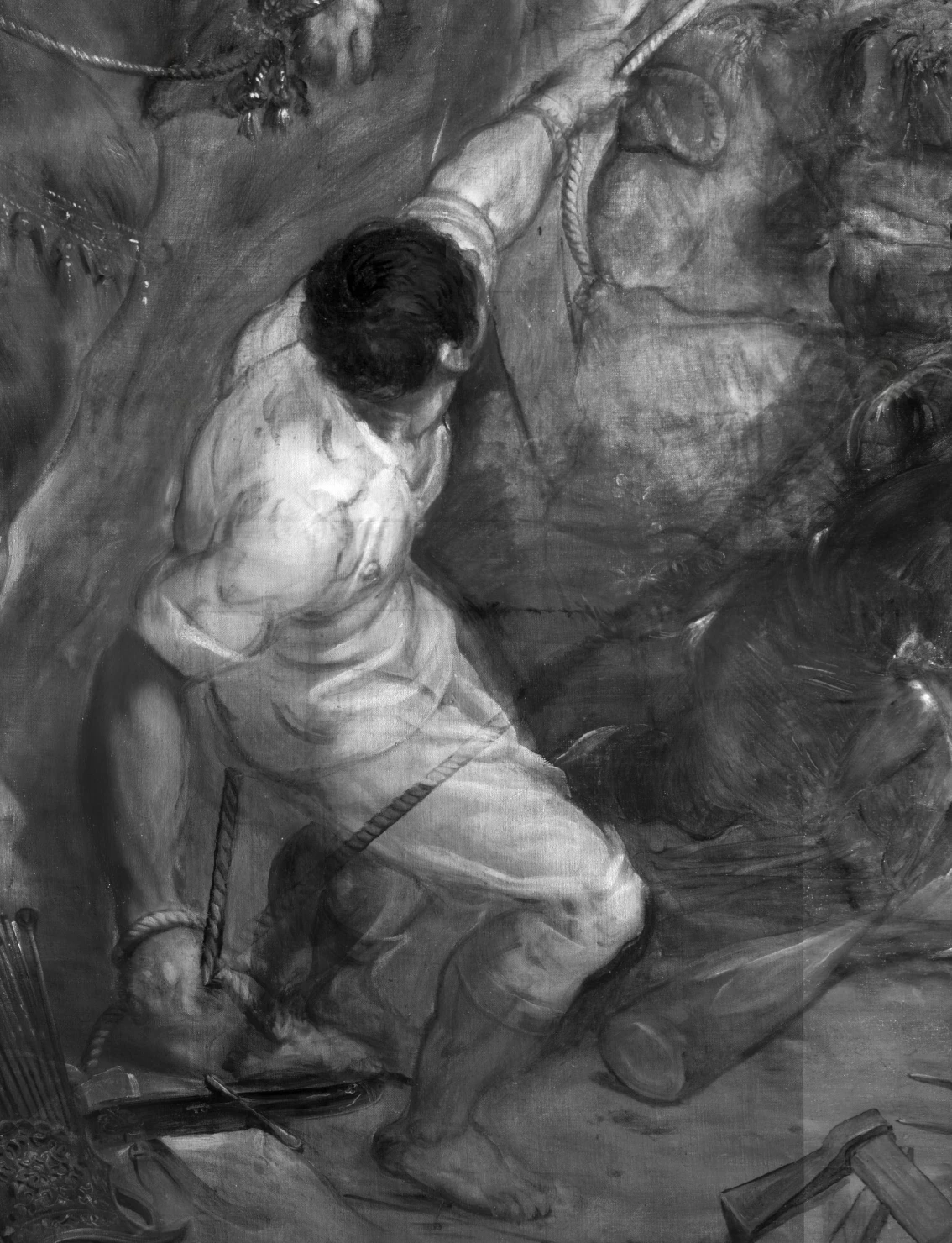

Reflectography, conducted with an InGaAs camera with a range of 1700 nm, revealed details not normally visible to the naked eye and provided insight on the artist's creative process. The painting was modified several times during its execution, from the initial underdrawings to the final pictorial phase, and corrections and changes can be seen that testify to the artist's constant search for formal and narrative balance.

These variations indicate focused interventions to redefine some details in the scene. Among these, one can cite the resizing of figures, the moving of objects such as the ladder or the right foot of the figure with the spade on the lower register, as well as the modification of the proportions of the cross and the arm of the old man near the "bad thief" about to be crucified. These are transformational operations in the passage from drawing to painting, to be distinguished from corrections made while painting, tied mainly to compositional and spatial exigencies. The early corrections reflect adjustments tied to gestural expressions and the need to progressively adapt the forms to the structure of the scene around them. The second series of corrections, instead, were made to harmonize the overall picture, improving the visual coherence and perspective

Some examples are significant: the rope pulling up the cross of the good thief on the left was initially painted in a lower position and later covered over and repainted in a higher position; this modification is related to the enlarging of the horizontal trunk of the cross, visible today because of the thinness of the paint layer. In the second register, some of the female figures were corrected, while the gestures of the figure on the horse to the right of the crucifixion scene changed completely. First the horseman had an upraised arm, which was later repainted with the arm much lower, near his pelvis. In the same section, the face of the man on horseback next to the flag, initially in the frontal position, was changed to a profile, giving more dynamics and coherence to the narrative scene.

Conservation Treatment

Enhanced and enriched by the aforementioned studies, the conservation treatment conducted by the CBC firm from 2023 to 2025 occurred with the Crucifixion remaining in its original location on the wall, with a three-story scaffolding erected in front of it. The painting was left in place because any attempts to roll or transport the Crucifixion could have caused additional damage to the artwork, and the canvas relining from the 1970s was still functional and did not require replacement.

The cleaning of the painting commenced with solubility tests to access the interaction of specific solvents to ensure that non-original substances could be safely removed without damaging the original paint layer. A low polarity solvent was used in this phase to remove compacted grime, discolored varnish, and more recent retouching. The oldest pictorial integrations were left in place to avoid further weakening the paint surface. In the delicate zones painted with bitumen and lakes pigments, solvents of different polarities were applied to correctly distinguish original layers from those added on top.

The cleaning phase addressed numerous alterations that compromised the painting's legibility. Nail holes along the border of the painting had been masked with gesso and glue fills of a brown-red color that also covered cuts and various losses. Damage was particularly evident on the yellow-orange drapes and folds of clothing painted with orpiment, a pigment made from arsenic sulfide that reacts to heat, humidity and light, and is vulnerable to both acid and base chemical compounds. These aspects, together with the way the paint was applied, the mixture used, and aggressive cleaning, explain why those areas suffer from flaking and partial or complete color losses. An example of lost orpiment is clear on the figure drilling the cross of the bad thief. His musculature, once veiled in yellow clothing, is now evident, revealing Tintoretto's characteristic brushstrokes. The sky, originally painted with smalt of an intense blue color, now appears as a very thin application of a brownish grey hue, due to the natural decaying process of the blue smalt pigment. Only the heavier highlights conserve their original color.

After non-original materials were removed from the surface during the cleaning process, the painting acquired better chromatic legibility. The canvas deformations progressively attenuated because the painting slowly regained its natural shape due to the elastic properties of the supporting canvases, and there was no need for more invasive interventions. Plaster fills were added to the areas of lost paint and homogenized and integrated with Bologna gesso and rabbit glue to imitate the surrounding canvas. Reversable pictorial integration, using the new plaster fills as a base so as to not come in contact directly with Tintoretto's painted surface, used conservation paints of the same tone, while abrasions were masked with colors similar to the undertones of the ground preparation. The conservation treatment concluded with an application of varnish applied both by brush and by spray, using a high stability resin of low molecular weight to guarantee the protection of the paint, as well as provide optical uniformity and the correct refraction range of the surface.

Following nearly 9000 hours dedicated to conservation efforts, the restored painting was inaugurated on April 12, 2025. Tintoretto's Crucifixion recovered compositional legibility and spatial depth without cancelling the traces of the complex conservation events that are part of its history. On the contrary, the cleaning and analyses undertaken gave the painting's extraordinary visual power a new clarity and at the same time provided research perspectives on Tintoretto's technique and the materials he used. The conservation treatment not only gave new life to one of the absolute masterpieces of the Venetian Renaissance but also offered an important contribution for a more profound understanding of Tintoretto's creative process.